A critique and a reply

‘Britain’s Weather in 2019: More of the Same, Again’ – Temperature Analysis Errors, by Alfie Hoar

The GWPF press release describes the key findings of the report as follows:

- After a rising trend between the 1980s and early 2000s, temperature trends have stabilised in the UK.

- Heatwaves are not becoming more intense, but extremely cold weather has become much

less common. - There is little in the way of long-term trends in rainfall in England and Wales.

- Sea-level rise around British coasts is not accelerating.[1]

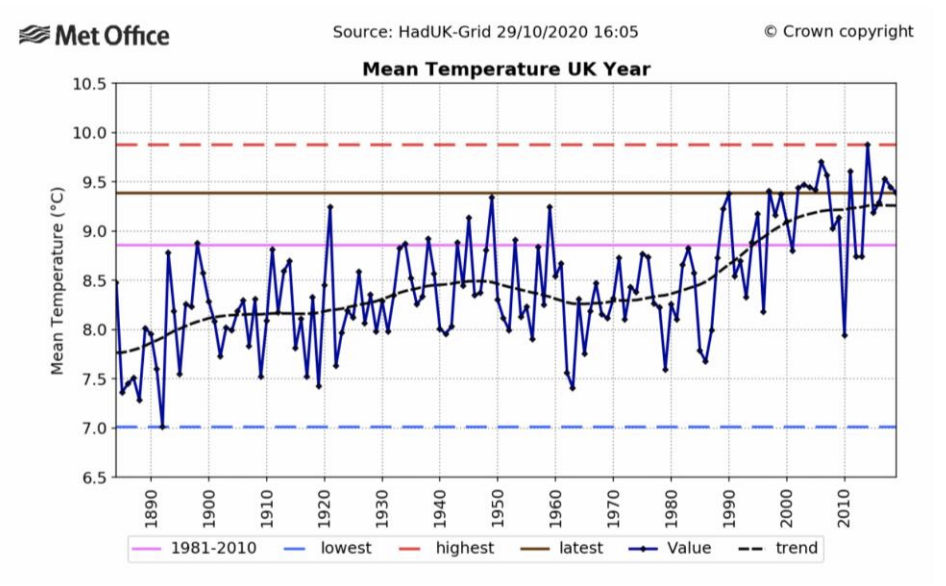

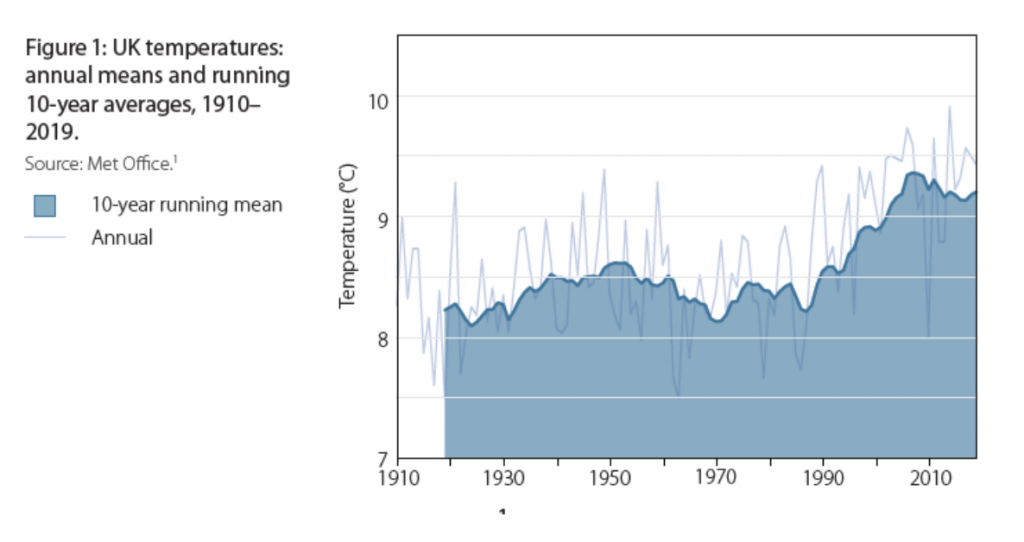

Both points 1 and 2 are misleading and inaccurate. For the first, if we look at the data records for the average annual temperature in the UK (Met Office Figure below [2]) we can see a warming trend from the 1880s to the present day. The statistical nature of temperature data means it will contain ‘noise’ – short term trend variations due the randomness of the physical mechanism from which the trends result. However, what is clear is that there is an overall warming trend, this simply cannot be disputed. If Mr Homewood was referring to the recent decrease in the rate of warming, then this is highly misleading. Firstly, changes in the rate of warming over short intervals have been seen throughout the period, this is simply the statistical ‘noise’ mentioned before. Secondly, to build conclusions of this short-term change is fundamentally unscientific, as it is understood in climatology that periods of around 15 years are simply too short to reach any meaningful conclusions on the temperature trends, and so it is unscientific to conclude that UK temperatures have ‘stabilised’.

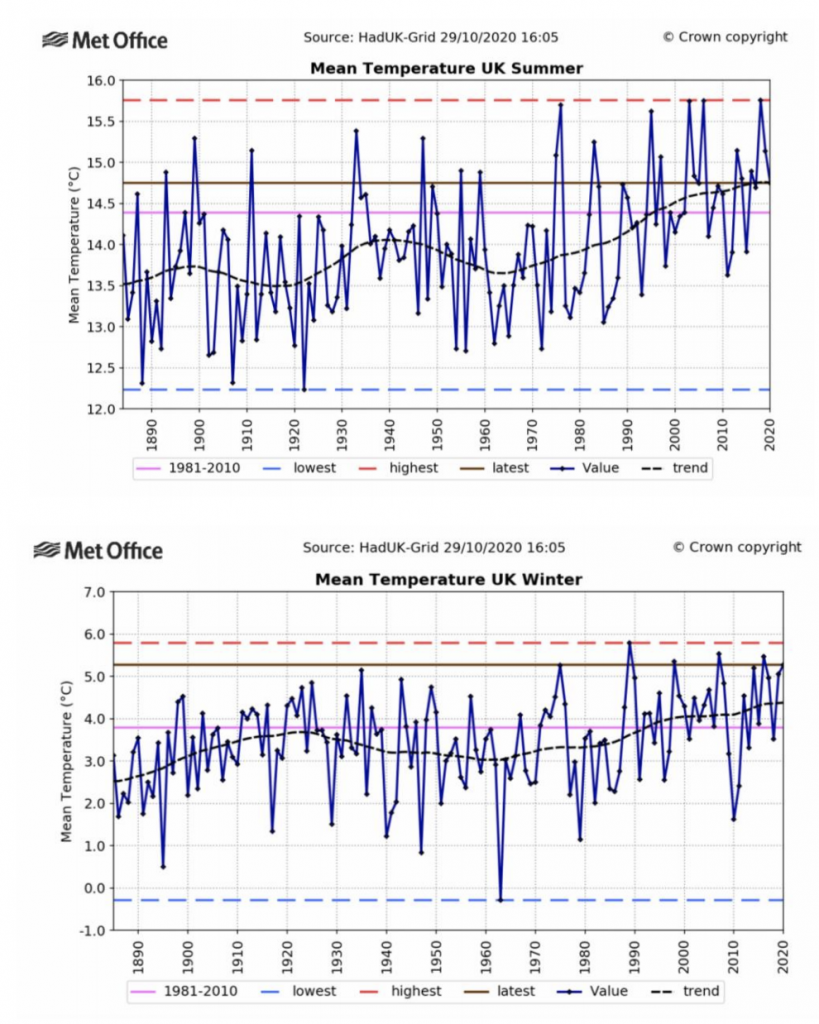

For the second key find, the idea that it is simply milder winters that are causing the warming temperatures again does not match the data. If we look at the average UK temperatures for the summer and winter (in Met Office Figures below [3]) we can see warming trends in both. As with the annual average UK temperature we can see statistical ‘noise’ in the data, but a trend of warming is present over this period. We can again also see a decrease in the rate of warming for both the UK average summer and winter temperatures, but this is not indicative of a ceasing of the warming trend which has been present over the whole period. The notion that summer temperatures are not increasing, and the overall warming is only due to milder winters, simply is not true.

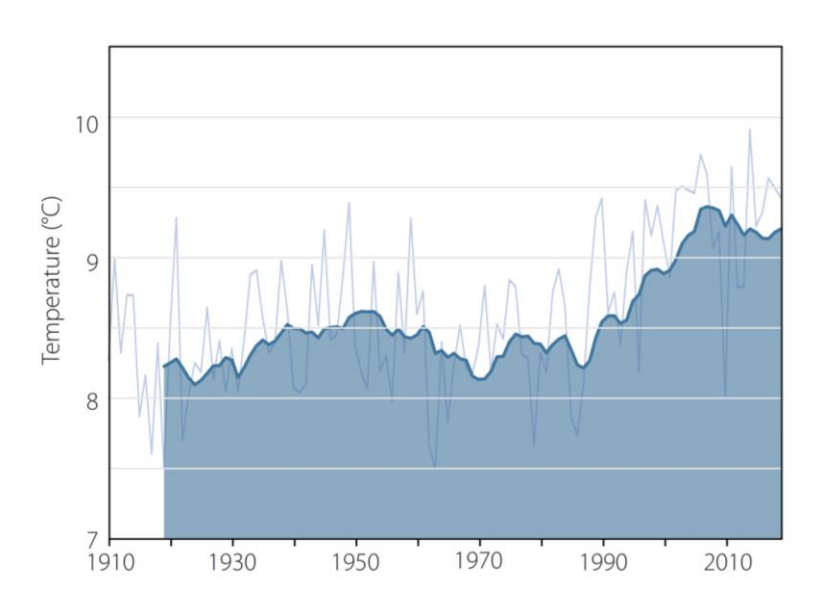

In the report itself Mr Homewood reiterates the idea of ‘stabilised’ temperatures in the UK, and describes how “the 10-year averages have been steadily declining since peaking in 2008.” This tells us little about the overall trend as 12 years is far too short a period to make any meaningful conclusions from. The data Mr Homewood is referring to here is presented in a graph below, and as with the previous graphs the ‘noise’ of temperature data is present here, but a warming trend over the period on the whole is still there.[4]

The short-term trends over periods of a decade or two simply are not an insight into the overall trend.

With regards to seasonal temperature trends, Mr Homewood states that “current winter temperatures appear to be barely higher than in the 1920s” which seems to contradict the key finding claim made in the article on the GWPF’s website. The data he presents in the report also demonstrates a clear warming trend for the average summer temperatures which also contradicts the claim made in the GWPF website article.

Now, Mr Homewood does state the following:

“Whilst temperature trends over the last two decades may not be significant in themselves, they do not support the theory that temperatures will rise sharply in decades to come.”

This claim is true, since the trends over recent decades cannot show us much about the overall trend, nor can they predict how short-term trends will change. Because of this, the data presented in this report also does not support the idea that temperatures have stabilised or will decrease over the next few decades – neither of these points were made by Mr Homewood. With this in mind, no meaningful conclusions can be made from the data picked out in this report. The key points mentioned on the GWPF’s website are unscientific, as are the points made by Mr Homewood mentioned above.

What is clear when we look at data over large time intervals is that there is a long-term warming trend for UK temperatures. Regardless of short-term shifts in the rate of warming, this long-term trend is going to continue based upon all the evidence we have. This point is not made by Mr Homewood, instead the report and the article on the GWPF’s website describe how UK temperatures have ‘stabilised’, which is not a scientifically sound conclusion to reach based on the data.

—————————

Reply by Paul Homewood

The comment by Mr Hoar relates to the GWPF Report, Britain’s Weather in 2019: More of the

Same Again, and consists of two separate criticisms

1) The report states that “After a rising trend between the 1980s and early

2000s, temperature trends have stabilised in the UK “

Mr Hoar complains that this is inaccurate because there is a warming trend from the 1880s to the present day, and that the lack of warming since the early 2000s is just a short term variation.

In fact the Report itself acknowledges this fact, stating clearly on Page 3:

“Whilst temperature trends over the last two decades may not be significant in themselves…”

However it also needs to be pointed out that most of the warming since the 1950s took place during the 1990s and early 2000s, an equally short period:

The fact that the UK is warmer than in 1880 tells us very little in any case. I am taller than I was when I was 10 years old, but does that mean I am still growing?

Equally, temperatures could remain unchanged for the next century, but the warming trend since 1880 would still be there.

It is therefore important to distinguish between “WAS” and “IS” in such matters. As such it is perfectly right and proper, as well as accurate, to report that temperatures have stabilised since the early 2000s.

2) The Report also states “Heatwaves are not becoming more intense, but

extremely cold weather has become much less common”

Referring to this, Mr Hoar states:

“the idea that it is simply milder winters that are causing the warming temperatures again does not match the data. If we look at the average UK temperatures for the summer and winter (in Met Office Figures below3) we can see warming trends in both.“

This is a straw man, as the report does not make this claim.

The section he refers to considers EXTREMES in temperature, not AVERAGES.

It analyses daily temperature data from the Central England Temperature Series, to investigate whether heatwaves and extreme cold spells are becoming more frequent or intense.

Furthermore, the Report goes into some detail about seasonal temperature trends, and specifically states:

“Seasonal temperature trends follow a similar pattern to the annual ones, with a steady rise during the 1980s and 90s, but little change since.”

Mr Hoar concludes by stating:

What is clear when we look at data over large time intervals is that there is a long-term warming trend for UK temperatures. Regardless of short-term shifts in the rate of warming, this long-term trend is going to continue based upon all the evidence we have.

This however is pure speculation. The purpose of the GWPF Report was to analyse the actual data, which it has done accurately and objectively

————————-

Alfie Hoar

I’m afraid Mr Homewood’s response does not remove my concern over his report. He is correct in pointing out that the period of fasting warming since the 1950s was the 1990s and early 2000s but this indicative of short-term variations due to the ‘noise’ in the data. These short term variations are present over the whole of the 20th century, but these tell us very little about the nature of temperature changes. What does tell us about how temperatures are changing is the long-term trends, and the long-term trend since the 1880s is one of warming.

Mr Homewood dismisses this in his response by stating that the fact that temperatures are warmer now than in the 1880s tells us very little, but it tells us a lot more than short-term trends. This is clear when one considers data over the whole period – short-term trends have very little predicting power because of their random nature, but long-term trends are not governed in the same way. For Mr Homewood to dismiss this and instead focus on the trend from the early 2000s to the present day to conclude temperatures have ‘stabilised’ is simply unscientific. By doing this, he is contradicting the vast majority of scientific literature on this topic, something the GWPF should make note of if they wish to continue publishing reports like this written by Mr Homewood.

His comment about my closing point – that the long-term trend will continue – describing as ‘speculation’ is fair in the sense that any prediction is speculation, but it is speculation based upon evidence.

As you wish to publish my criticism and Mr Homewood’s response, I would urge you and Mr Homewood to reconsider his point about my first criticism. His notion that long-term trends cannot tell us very much just isn’t scientifically sound – the context of trends matters massively with data like this, and it is clear when looking at the data available that long-terms have more predicting power about how our weather is going change over many decades than short-term trends do. Nor do short-term trends have much predicting power about how temperatures will change in the short-term, as can be seen when we look at the data by the rapid change in short-term trends in the past.

I would further ask you to consider all of this within the context of my original concern – the nature of the GWPF’s Academic Advisory Council. The Council are not representative of the scientific community on this topic, and nor is Mr Homewood’s report. Mr Homewood’s report contains some very contrarian conclusions in it, and I feel if the GWPF wishes to represent his report and my criticism fairly then it must put these into the context of the wider scientific literature.